THURLBY CHURCH, LINCOLNSHIRE

An old church is like an old house, or an old tree, a link still living with people and scenes of long ago. Its walls have a story to tell of our forefathers, our own kindred, whose place we are now taking. There are houses that have come down from father to son, father to son, for generations, something altered here, and added there.

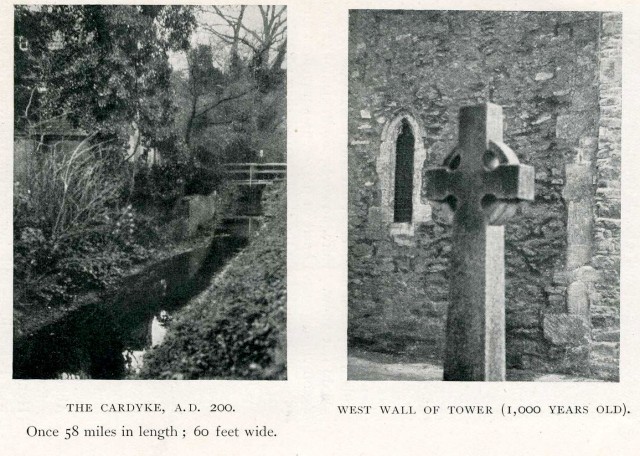

An old church is a house for worship and prayer that has been inhabited age after age by the same family. Only there are not many houses so old as this church. Come round here to the tower outside. That ditch which skirts the churchyard to the west was once a fine Roman canal. It ran from Peterborough to join the Witham near Lincoln. It was 60 feet wide from bank to bank. Along it have passed in turn Roman centurions, Saxon invaders, Danish pirates, and perhaps Plantagenet kings. Somewhere about the time when Roman engineers were cutting this canal, the Cardyke, there was a Bishop of Amiens in France, a native of Navarre, named Firmin. He is said to have suffered martyrdom a.d. 250, when Decius was Emperor. Well, the great canal with its boats and barges, coracles and ships of war, has gone. One by one the generations of men and women have come and gone, as we shall go. But here beside the Cardyke stands the church whose bells ring out week by week over the Lincolnshire Fens, and it bears the name of that very Bishop Firmin. Such changes have the centuries wrought, and so far back do its memories reach, to the days of those masterful people who once very capably ruled this island. Now turn to the tower. Its walls look solid as rock. Notice the big stones laid endwise and lengthwise up the angles. They were brought along the Cardyke from Barnac. We have come a long distance from Roman days.

A settlement had been formed in the bush and woodland to which one Turolf gave his name. This settlement was now to have its tower and church—the church for worship, the tower adjoining for watching and refuge. Fair-haired Saxons, suffering greatly from Danish raiders, laid these stones. A belfry, you know, does not mean a place for bells. It means a place for shelter, and if there was a bell it was used to give warning as well as to call to prayer. This was a belfry. It was built just about the time when Edward, son of the great Alfred, died, AD 925, and close on a century before William the Norman was born. England was in the throes of its making. The tower has seen a thousand chequered years. Who can tell what it has yet to see ?

Let us go inside the church and look again at the tower. We shall notice the stones of a wide archway above the tower arch. They are part of the Saxon church, and they may date from the reign of Canute. He died in 1036. Higher up in the wall you see a triangular recess. This was a doorway into the tower, to which people climbed in case of danger. No doubt it could tell of more than one sudden alarm, when a glow that meant burning homestead or abbey was seen in the sky. If you care to go up the ladder —it is a rather shaky relic, and beware the trapdoor—you will find on one of the jambs of this doorway, carved on the stone, the head of a ” Viking.” It is much worn, but there he is, in his winged helmet, and the face with its resolute chin and heavy moustache is the face of a warrior. Is he Turolf, the founder of Thurlby, or who is he ? Nobody knows. But that small carving is the only one of its kind. Of itself it takes us back to the days of those fierce seafarers who laid the foundations of England’s power.

At the time of the Domesday Survey—1086—the Abbey of Peterborough held the Manor of Turolvebi and over 600 acres of land assessable to Danegelt, of which part had been held by Elrod,under Aslac. This Aslac had ” built a bridge in the causeway into Holland.” It is most likely to Ernulf, Abbot of Peterborough, that we owe the Norman portions of the church. He was very much beloved, and the king—Henry I, brother of Rufus—afterwards insisted that, whether he liked it or not, Ernulf should become Bishop of Rochester. He had previously been Prior of Canterbury.

Let us look at the massive font. It is of Barnac stone and used to be coloured. A patch or two of colour is left. Here for 800 years without a break Thurlby people have been baptized. The font, the arch behind it, the four westerly columns in the nave, and the south doorway were built at this time, and consecrated in 1112, a year of a splendid harvest, by Robert Bloet, Bishop of Lincoln, the same Robert who ten years later was suddenly stricken by death while riding with the king in Woodstock Park.

On the westernmost pillar to the south you will find a recess about 6 inches long. This may have been a little shrine, and its position here may have something to do with St. Firmin’s Day, September 25, by the angle which on that day it -makes with the sun. Ernulf’s church was shorter than this, with a semicircular east end. You will see in the south wall of the chancel a fine Norman arch with dog-tooth ornament. This was part of his church, but why it was placed here we do not know. Here, however, Norman monks and Saxon villagers have knelt in prayer, and travellers and pilgrims up and down the Cardyke paid their vows.

In 1154 Henry II. became king, and the next year William de Waterville, “a good clerk,” Abbot of Peterborough. Henry visited Peterborough and Spalding, too. Did he go by water and pass Thurlby on his way? If so, that violent and able king, with the fiery face and tremendous oaths, who terrified most people but not Hugh of Lincoln, may have passed through the southern doorway.

It was Abbot de Waterville who founded near Stamford a Sisterhood, the Priory of St. Michael, and endowed it with the benefice of Thurlby on payment of half a silver mark yearly to the Chanters of the Abbey and 10s to the Sacrist.

Some fifty years later, about 1230, when King Henry III. was twenty-three, the Prioress—her name was Petronilla—and her Sisters resolved to enlarge Thurlby Church. They were not rich, and no doubt the people of Thurlby one and all, owners of land and labourers, helped largely, often working with their own hands. The Abbey too may have assisted. One likes to think of the Prioress in wimple and veil coming from Stamford, perhaps along the Roman road we call Kingston Street, perhaps on the Cardyke, to interview steward and workmen. A great deal was done. Men’s motives are usually mixed. Partly from a single-hearted wish to glorify God, partly for the pleasure of building, partly with the idea of making some satisfaction or compensation for their misdeeds, they set about a task that we in these days should hardly think of undertaking. The Norman chancel was lengthened, and a small wing or aisle added on each side of it. Three tall single or lancet windows were inserted in the east wall, and two on the north and the south. The present chancel arch was built and the transepts enlarged, the arcading which we see being carried first round one and then a little later round the other. Both transepts had a space for an altar, and in one, the floor of which used to be lower, is a bracket for a cresset or torch, and a pedestal for a statue. Two aumbries or cupboards were provided in the chancel, one on the floor close beside the high altar, for relics perhaps, and the other as a sepulchre for the Host on Good Friday. The large piscina and pointed recess, which looks rather like a walled-up doorway, next it, on the south side, are of the same date.

The shields of arms are of King Henry VI., the founder of Eton; King Henry VIII., who transferred to Eton the Thurlby property of St. Michael’s Priory ; and of his present Majesty, who gives the parish the Royal Bounty; and opposite, the Abbey of Peterborough, the Priory of Our Lady and St. Michael, and Eton College. Other shields in the church are of families formerly connected with the parish, as noted by Gervase Holies in 1634—viz., De la Mare, Wasteneys, Lucy, Wake, Mallory, Crumwell, Driby, and others, including .

One would like to suppose that the face above one of the capitals she altered is a portrait of the Prioress Petronilla. We owe to her in addition one porch, if not both, where people would leave tools, weapons, and so on before entering the church, and where, too, the coroner would sometimes hold an inquest. Notice the stone on a bench in the north porch. The marks and tracing on it are evidently a sort of stellar diagram. You can recognize the Belt of Orion. It was found in the chancel floor. Had it something to do with astrology ?

Let us go to the beautiful little chapel we know as the south chantry. There are four windows to our right, each of some interest. The first, which is square, is the low side or leper window. One would be glad to think it true that here those poor souls, the lepers, came to listen from outside to the service and receive the Sacrament. But lepers were not allowed anywhere near. They were treated as dead. At this window you are in line with the “squint” or opening through the chancel wall by which a glimpse can be had of the priest at the centre of the high altar. There is a second squint in the northern wall.

The great and dramatic moment to which the worship of the Middle Ages led up was the Elevation of the Host. Bells were rung. The worshippers all fell upon their knees. The Divine Presence they believed was among them. Someone waiting by this window could see the priest and give the signal. The window above perhaps belonged to a cell. It is made of one single stone. The large window, of later date, looks as if it had been squeezed into its place, as you can see from outside. It is of curious construction. Above is a hood shaped like a horseshoe. The delightful little lancet by the altar was inserted when a bigger window was filled in.

It is easy to picture those who first worshipped in the chantry—smock-frocked countrymen, fowlers and fishers from the fen, whose dust lies in the churchyard, sandalled pilgrims wending to and fro to Lincoln or Walsingham, or, further still, Rome and the Holy Land. People travelled about more in those days than till lately they have done since. Now and then came a merchant with his bales of wool, or a knight and his retinue, or one or two friars, not over welcome to the Vicar, bent on their task of revival.

Another century passed. Thurlby Church was again enlarged and beautified. We have come far from Saxon and Viking. Edward III. is on the throne. The wool trade is flourishing and bringing England, especially the Eastern Counties, wealth. The cloth trade is feeling its feet. Edward was married in York Minster in January, 1327, and Philippa of Hainault, his bride, spent that New Year’s Day at Peterborough on her wedding journey north. She may have passed through Thurlby.

In 1348 occurred that fearful catastrophe, the Black Death. It destroyed entire villages. The Sisterhood of St. Michael suffered terribly, all but one of its members dying or being dispersed in the upheaval. For this reason, probably, it was united to another Stamford community, St. Mary’s, in 1354.

In 1359 the head of the united communities was the Prioress Agnes of Braceburgh, and to her we owe the chapel to the north of the chancel we call the Eton chantry. It was for a while used as the village school, and is now the Children’s Chapel. The tracery of its windows is of rather uncommon design. Here there are two piscinas —one for washing the altar vessels, the other, forming part of the ” squint,” for the minister’s hands. You can see the marks of his towel-rail. The three single windows above the high altar were changed into one big window. Some of the nave windows were enarged, and others inserted. These, with the row of quaint carvings along the cornice, are best seen from outside. Above all, the spire was added to the tower. It has four very large spouts or gargoyles, and several dormers and crosses. The battlementing on the parapets was added and the two side wings to the tower were raised. A number of ready-made grave slabs were found in use as flooring for the gutters.

What the Prioress Agnes left the church it has remained. But fifty years or so later the east window showed signs of weakness and its stonework was replaced, while a very fine chancel screen of carved and painted oak with overhanging cornice was set across the chancel arch. There were smaller screens for the chantries and transept. This has most of it gone. Some of its timbers were used for joists and rafters. The doorway is conspicuous over the pulpit.

The Church was then in full splendour. Columns and walls glowed everywhere with colour. The screen, a bridge of colour, with its tall crucifix, spanned the arch. Each of the five altars had its rich hangings and its lights. Here and there stood a painted statue. The windows, or some of them, were many hued. Some fragments of the glass were found in a cavity of the west wall. There were no pews, choir stalls, or organ. The pavement, perhaps, was strewn with rushes.

Look, before you go further, at the will of John Sawer, of Thurlby, in 1521. It hangs on the south wall. With its gift ” for thynges forgotten,” and its mention of the ” gylde the mynstrelles kepe,” it has a true beauty and pathos of its own.

It is sad to read the story of devastation reported in 1566 to the Archdeacon of Lincoln. The figures on the screen were burnt- The altars were turned into stiles for the churchyard. An enamelled sepulchre—today it would be priceless—was given to the glazier. Candlesticks, cross staff and censers were sold to John Townsend, a tinker of Haconby. Bells were melted, banners were cut to pieces, and what is not named probably stolen.

When the Priory with which Thurlby was so long connected was dissolved by Henry VIII, the benefice with its revenues was granted to Eton College. They have ever since enjoyed the larger share of its income.

Turn to the westernmost window of the north aisle. It is unlike the rest, and interesting as the latest bit of building—a rough imitation of older and better work. It dates from just about the time when Townsend the tinker was haggling over the price of candlesticks, 1565. At any rate, it carries us another stage to the days of redoubtable Elizabeth.

The people of each of those six centuries from 924 onwards have left us their mark. But we can go further still.

In 1602 the church is described as ” in good repayre and decent kept, though the chansell is in decay.”

Soon after, in 1616, the chalice and cover we are using were obtained. The delightful altar-rails—see how they were turned by eye, and not all according to pattern—and the fine cane-seated chair are memorials of the ill-fated Charles I. and Laud, his Archbishop.

Look at the windows in the nave. Their upper tracery has been hacked away to save trouble in glazing. That is a significant bequest of Commonwealth rule, when what was left of the painted glass was smashed, and people liked to show scorn for beauty and antiquity. Times changed again, and the great Bible and Prayer Book on the lectern was given to celebrate the return of Charles II.

The bells commemorate, as an inscription in very odd Latin tells us, the victories of Marlborough under Queen Anne and the famous Peace of Utrecht, 1713, while the silver flagon and plate for the altar were the gift of Miss Ann Fisher, a notable friend to Thurlby, in 1762.

The nineteenth century made its contribution in extensive alterations carried out by the Rev. C. P. Worsley, and in a memorial pulpit and stalls, and the twentieth in a high altar not unworthy of the church, which commemorates the war of 1914-1918 and two of those whose lives were given for King and country.

England, which is much richer for its country churches than it knows, has many larger and many with more important associations or features of more outstanding value. But it has not many with a longer history than this, and fewer still that can show like this, in regular succession, the handiwork of so many generations of our forefathers.

[The writer’s thanks are due to Colonel Sir Alfred Welby, who has helped in the revision of these notes.]

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY BILLING AND SONS LTD., GUILDFORD AND ESHER